The making of the first modern Hindi thesaurus

Arvind Kumar goes down memory lane, recalling the many challenges he faced while compiling “Samantar Kosh”

By Nilima Pathak (Special to Weekend Review)

Published: 21:30 April 10, 2014

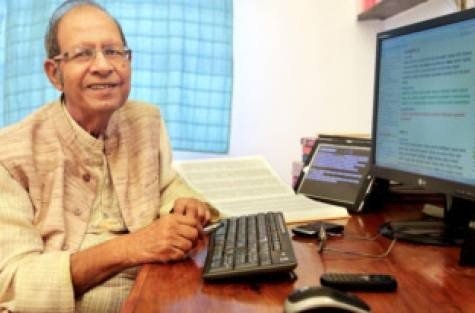

A godsend Kumar was struggling to compile his massive collection of words, and a computerised database was just what he needed

Arvind Kumar is the Peter Mark Roget of India if you like, for he has created India’s first-ever modern Hindi thesaurus, “Samantar Kosh” (dictionary of parallel expressions). The technological advances since Roget’s times have enabled him to go a little further. The online version, a bilingual Hindi-English-Hindi thesaurus, is available at arvindkumar.me and also offers Hindi words in Roman script for those who cannot read Hindi. The thesaurus is now available in a format that can be accessed through android devices.

“Following in the footsteps of the British physician and lexicographer, who published ‘Roget’s Thesaurus’, comprising English words and phrases, was a conscious decision,” Kumar says.

At 84, Kumar is still at it, working to expand his lexicon of words in Hindi in his mission is to help millions to learn and improve India’s national language.

Recalling his initiation into the work, he says: “Coming from a humble background, I had been working to supplement my father’s small income after finishing tenth grade in 1945; I was a bright student, with distinctions in four subjects — Hindi, Sanskrit, English and Mathematics. At the Delhi Press that churns out several magazines, I would spend hours replacing lead typefaces in the compositor’s trays, before going on to become a cashier, typesetter, proofreader and subeditor.

“In 1952, when I was 22 years old, I was shifted from a Hindi magazine to an English publication. And that’s the time I was introduced to the first edition of ‘Roget’s Thesaurus’ to look for appropriate alternative words of expression. It was a whole new world for me and I wondered why no one had thought of something similar for Hindi and began thinking along those lines.”

With a bit of research, Kumar discovered that ancient India had a fledgling tradition of lexicography. These included “Nighantu”, Kashyap’s thesaurus of 1800 Vedic words, and Amar Singh’s celebrated 8,000-word Sanskrit thesaurus “Amar Kosh”, compiled before the 10th century AD. But family and work forced Kumar to put all thoughts of a Hindi thesaurus on the backburner.

In 1963, he quit as executive director for all magazines at Delhi Press and moved to Mumbai as editor of Madhuri, a Hindi film magazine of the Times of India group. With Kumar’s journalistic expertise, the magazine, launched by him, became a hit. “It was not a run-of-the-mill film magazine. I experimented with and focused on features related to the art of cinema-making, how films were shot, and the unnoticed ‘extras’ who contributed to a movie.”

Though all this was fulfilling, after a point, the parties and premieres, late nights and endless working hours left him with little time for his family. A decade had gone by in this fashion, and the idea of the Hindi thesaurus began pricking him once again.

“I shared my thoughts with my wife Kusum, telling her that I planned to quit the job after few years,” Kumar says. “The only factor that held me back was our children Sumeet and Meeta’s studies, both of whom were in school then.”

Kusum agreed, because she knew the venture was close to his heart. In 1978, the family moved back to Delhi. Kumar began collecting Hindi dictionaries and reference material to proceed with his project.

“I wanted a systematic format for my thesaurus similar to that of ‘Roget’s’. I began writing down words on small ruled cards that could be numbered according to Roget’s system. For example: under the group taste, if ‘sweetness’ was number 1, then ‘saltishness’ was number 2). Kusum too would assist me and we thought all we had to do was write appropriate Hindi equivalents or synonyms and the job would be done in maximum two years,” he says.

But Kumar was in for a shock. He discovered that many words and concepts were missing in ‘Roget’s’ and had no clue how he could fit in hundreds of concepts in between the already numbered cards. In ‘Roget’s’, each concept has its own logical place. But as Kumar picked up the Indian concepts, he found there were no equivalents in English for numerous words. In addition, some words such as ‘haldi’ (turmeric) had over 125 Hindi synonyms!

He explains: “There are numerous quirky coinages such as ‘chinia Badam’ and ‘bhotia Badam’ that refer to peanuts, or ‘chimta’ — the front-wheel holder in a bicycle, coined by the ubiquitous roadside repairer. So, I had to jot down millions of words and going deep down into the roots of Indian culture, find a place for classical expressions such as ‘abhisarika’ for ‘rendezvous heroine’. The task started becoming difficult by the hour. Every time I thought we were inching towards success, we would go many kilometres back!”

In between all this, Kumar and his family went through several ups and downs. “Two years had gone by, but it seemed we had just begun work! Finances were becoming an issue, so I was forced to take up a job,” he says.

He joined Sarvottam, the Hindi edition of Reader’s Digest, in 1980, where he spent five years, before resuming full-time work on the thesaurus. By 1990, he had 60,000 cards with more than 2,50,000 handwritten words that filled 70 trays. And in the next one year, the number rose to 3,50,000 Hindi words. More problems surfaced. Assigning numbers to different concepts by hand was not only becoming tedious, but it also became impossible to keep track of all the words he had noted down.

Mounting pressure took a toll on Kumar’s health and he suffered a heart attack. Fortunately, his son, Sumeet, who had by then become a doctor, took charge of the family’s finances and advised him to take it easy. Around then, Kumar also found a publisher for his thesaurus.

But given his experience with printing and publishing, he was worried about typists mixing up the sequence of his cards or misplacing them. They could even make spelling errors that would change the entire meaning of a word or could mix up the type sheets and add more errors, he thought. “After years of compilation, we found that the result could be disastrous if everything got jumbled up. That’s when my son suggested we should computerise all the data,” Kumar recalls.

Back then, the cost of a new personal computer and software was more than Rs100,000 (Dh6,100 today). That was a huge amount in the early 1990s and Kumar did not know where the money would come from. Sumeet took up a job at a hospital in Iran and saved enough to return home with a computer. He also taught himself computer programming to help out his father.

The entire scenario changed once they had the computerised database. It not only became easier to make additions, but any duplication would also show up. Years of work was indexed with the help of a data entry operator and made ready for press.

National Book Trust, a Government of India undertaking, published the first edition of the Hindi thesaurus in 1996. And the first copy of “Samantar Kosh” was presented to then president Shankar Dayal Sharma in a ceremony at the president’s residence. Receiving rave reviews, it became an instant hit with writers, journalists, advertising copywriters, teachers and students. Since then, the book containing 1,60,850 expressions grouped in 1,100 categories and 23,759 sub-categories has seen six reprints. It is now marketed by Arvind Linguistics.

Kumar then set himself new targets. With the help of his daughter, who had become a nutritionist, he began adding English expressions to his data, which took another decade. “The Penguin English-Hindi/Hindi-English Thesaurus & Dictionary” was published in three volumes in 2007. The world’s largest bilingual thesaurus has 3,200 pages and weighs five kilograms.

“In keeping with modernity, we have been upgrading our work,” says Kumar, who has received numerous awards and accolades, including Shalaka Samman (Hindi Academy, Delhi), Subramanyam Bharati Award (Kendriya Hindi Sansthan, Agra), Akhil Bharati Hindi Sewa Puraskar (Maharashtra Rajya Hindi Academy) and Dr Hardev Bahri Samman (Hindi Sahitya Sammelan).

What next? “I will try to add all major Indian languages, starting with Tamil, to my vast records,” the octogenarian says. “A new computer application worked out by my son is capable of producing a multi-language thesaurus involving several foreign languages. In addition, I am working on the much-needed dictionary of Hindi rhymes.”

Nilima Pathak is a journalist based in New Delhi.

Comments