Abhishek Avtans and Arvind Kumar

Central Institute of Hindi, Agra

Email: abhiavtans@gmail.com and samantarkosh@gmail.com

Introduction

Indian linguistic area as envisaged by late Prof MB Emeneau in his seminal paper entitled ‘India as Linguistic Area’ (1956) is home to a total of 234 mother tongues with over ten thousands speakers (2001 Census) and numerous smaller and lesser known languages belonging to at least five major language families viz the Indo Aryan, Dravidian, Tibeto-Burman, Austro Asiatic and Andamanese spoken by a vast population spread across Indian subcontinent. Not going much deep into the reasons, it is important to mention that the number of mother tongues which are accounted in the census data have seen an increase from 184 in 1991 to 234 in 2001. Notwithstanding the conservative estimate of Ethnologue (2008) that 20 percent of world’s living languages are moribund including the ones spoken in India, this increase in number of mother tongues has shown us the ray of hope by increasingly visible assertion by people to identify with their languages. Surprisingly the situation for Indo Aryan language family with almost 15 languages out of the 22 recognized in the eighth schedule of the constitution of India does not seem to be too well with respect to its smaller and lesser known members. Gradually many of these lesser known languages are losing their speakers in face of bigger and mightier languages and eventually dying an unnatural death resulting in loss of precious bio-cultural knowledge accumulated over many centuries. One of the measures to counter this unwanted situation is the centuries-old practice of building grammars and dictionaries. It is true that complete language revitalization cannot be achieved by mere preparation of grammars and dictionary. There is lot more which needs to be done in this respect. However it is sure that development of these resources paves the way for wider community involvement and awareness culminating in the preservation of the precious traditional knowledge for future generations.

In this paper we are concerned with development of lexical resources for varieties of Hindi. This paper discusses the nuts and bolts of creation of modern lexical resources for varieties of Hindi viz Bhojpuri, Brajbhasha and Rajasthani (Marwari) under the ongoing project ‘Hindi Lok Shabdakosh Pariyojana’ (henceforth HLSP) of Central Institute of Hindi, Agra. Apart from some individual efforts in the last century, so far this project has been the only institutional effort aiming to document and prepare lexical resources of all varieties of Hindi using state of art lexicographical tools and methodologies. In order to reach wider readership and usage, the project envisages to build trilingual dictionaries (Variety-Hindi-English) in both print as well as web mounted digital formats. Starting with a short survey of earlier lexicographical work done on varieties of Hindi, the paper presents the methodology adopted for lexical documentation and compilation of dictionaries for the above-mentioned languages. The paper also discusses the software applications viz. Summer Institute of Linguistics’ FieldWorks Language Explorer 2.0 (in short Flex) and Lexique Pro 2.8.6 used in the project for developing these lexical resources.

Hindi and its varieties

Hindi is an Indo-Aryan language (a branch of the Indo-European family of languages) which is considered to be the fifth most widely spoken language of the world. It is spoken primarily in the so-called ‘Hindi Belt’ states of Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Delhi, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttarakhand, and Uttar Pradesh. Besides being the official language of these states, it is also one of the two official languages of government of India along with English. Although not insignificant number of speakers of the language can be found across Indian non-standard but distinctive varieties of the language are also spoken by large populations in megapolices of Kolkata, Mumbai and Hyderabad and now increasingly in Chennai, Bangalore and Pune. According to the 2001 census, it is spoken by 422,048,642 speakers which include the speakers of its various varieties and variations of speech grouped under Hindi. It is also spoken by a large population of Indian diaspora settled not only across countries such Guyana, Surinam, Trinidad and Tobago, Fiji, Mauritius and South Africa, but also in Europe, North America, Australia and Middle East.

The issue of enumerating and classifying varieties (or dialects[1]) of Hindi has always been complex and onerous task for scholars objectively dealing with Hindi linguistic space. Grierson (1906) has divided Hindi into two groups: Eastern Hindi and Western Hindi. Between the Eastern and the Western Prakrits there was an intermediate Prakrit called Ardhamagadhi. The modern representative of the corresponding Apabhransh is Eastern Hindi and the Shaurseni Apabhransh of the middle Doab is the parent of Western Hindi. In the Eastern group Grierson discusses three varieties: Awadhi, Bagheli, and Chattisgarhi. In the Western group, he discusses five varieties: Hindustani, Brajbhasha, Kanauji, Bundeli, and Bhojpuri. Eastern Hindi is bound on the north by the languages of Nepal and on the west by various varieties of Western Hindi, of which the principal are Kannauji and Bundeli. On the east, it is bound by the Bhojpuri variety under Bihari group and by Oriya. On the South it meets forms of the Marathi language. Western Hindi extends to the foot of the Himalayas on the north, south to the valley of Yamuna, and occupies most of Bundelkhand and a part of central India on the east side.

The Hindi region is traditionally divided into two groups: Eastern Hindi and Western Hindi. The main varieties of Eastern Hindi are Awadhi (north-central and central Uttar Pradesh), Bagheli (north-central Madhya Pradesh and south-central Uttar Pradesh) and Chattisgarhi (south-east Madhya Pradesh and northern and central Chhattisgarh). The Western Hindi varieties are Haryanvi or Bangaru (Haryana and some areas of National Capital Region), Brajbhasha (western Uttar Pradesh and adjoining districts in Rajasthan and Haryana), Bundeli (west central Madhya Pradesh), Kanauji (west-central Uttar Pradesh) and vernacular Hindustani or Kauravi (spoken in north and northeast of Delhi. The varieties spoken in the regions of Bihar (Maithili[2], Bhojpuri, Magahi etc.), in Rajasthan (Marwari, Mewari, Malvi etc.) and some varieties spoken in the northwestern areas of Uttar Pradesh (Garhwali, Kumauni etc), and Himachal Pradesh (PahaRi) were separated from Hindi proper (Shapiro, 2003). Now, all of these varieties are also covered under the label Hindi. The standard variety of Hindi recognised by the government and promulgated by its various agencies is based on a western variety commonly known as Khari Boli (established speech) which has a history of long established educated use in the urban centres of north India (McGregor 1972).

Dakhini is another variety which deserves mention (also considered a variety of Urdu, a sister language of Hindi). It is spoken in Hyderabad (capital of modern state of Andhra Pradesh) and other areas of Deccan plateau primarily by Muslim populations (Masica 1991). Hindi as an umbrella term is not only used to identify languages of the above two major groups but also for the languages which were traditionally out of its purview such as Bihari and Rajasthani varieties.

Indian census of the year 2001 identifies 49 different varieties/languages of Hindi under the label Hindi (including Hindi itself). This count of 49 varieties excludes various smaller varieties like Angika (spoken in Bihar and Jharkhand), Kavarasi (spoken by Kavar community of Jharkhand), Dakhini (Hyderabad and Deccan Plateau), Kannauji (west-central Uttar Pradesh), Bajjika (spoken in Muzafafrpur and Vaishali, Bihar), Koshika (spoken in Purnea, Saharsa and Farbisganj Bihar), Tharo (spoken in neighboring areas of Nepal and Bihar), Halbi (spoken in Bastar, Chattisgarh), Lariya (spoken in Mahasamund and adjoining areas, Chattisgarh), Kashika (spoken in Varanasi, UP) etc spoken by well over 14,777,266 speakers (classified as others in Census 2001). Table 1 presents the list of varieties of Hindi and number of their speakers as enumerated by Census 2001.

Table 1: Varieties of Hindi (Census 2001)

|

Languages and mother tongues grouped under Hindi |

Number of speakers |

|

Hindi |

422,048,642 |

|

1. Awadhi |

2,529,308 |

|

2. Bagheli/Baghel Khandi |

2,865,011 |

|

3. Bagri Rajasthani |

1,434,123 |

|

4. Banjari |

1,259,821 |

|

5. Bhadrawahi |

66,918 |

|

6. Bharmauri/ Gaddi |

66,246 |

|

7. Bhojpuri |

33,099,497 |

|

8. Brajbhasha |

574,245 |

|

9. Bundeli/ Bundelkhandi |

3,072,147 |

|

10. Chambeli |

126,589 |

|

11. Chhattisgarhi |

13,260,186 |

|

12. Churahi |

61,199 |

|

13. Dhundhari |

1,871,130 |

|

14. Garhwali |

2,267,314 |

|

15. Gojri |

762,332 |

|

16. Harauti |

2,462,867 |

|

17. Haryanvi |

7,997,192 |

|

18. Hindi |

257,919,635 |

|

19. Jaunsari |

114,733 |

|

20. Kangri |

1,122,843 |

|

21. Khairari |

11,937 |

|

22. Khari Boli |

47,730 |

|

23. Khortha/ Khotta |

4,725,927 |

|

24. Kulvi |

170,770 |

|

25. Kumauni |

2,003,783 |

|

26. Kurmali Thar |

425,920 |

|

27. Labani |

22,162 |

|

28. Lamani/ Lambadi |

2,707,562 |

|

29. Laria |

67,697 |

|

30. Lodhi |

139,321 |

|

31. Magadhi/ Magahi |

13,978,565 |

|

32. Malvi |

5,565,167 |

|

33. Mandeali |

611,930 |

|

34. Marwari |

7,936,183 |

|

35. Mewari |

5,091,697 |

|

36. Mewati |

645,291 |

|

37. Nagpuria |

1,242,586 |

|

38. Nimadi |

2,148,146 |

|

39. PahaRi |

2,832,825 |

|

40. Panch Pargania |

193,769 |

|

41. Pangwali |

16,285 |

|

42. Pawari/ Powari |

425,745 |

|

43. Rajasthani |

18,355,613 |

|

44. Sadan/ Sadri |

2,044,776 |

|

45. Sirmauri |

31,144 |

|

46. Sondwari |

59,221 |

|

47. Sugali |

160,736 |

|

48. Surgujia |

1,458,533 |

|

49. Surjapuri |

1,217,019 |

|

Others |

14,777,266 |

Lexicography for Mothers: What has been done so far?

In a narrow sense lexicography can be defined as the art and craft of dictionary making, i.e., development of lexical resources. From Rosetta stone[3] of 196 BC to the digital dictionaries of 21st century, lexicography as a discipline has travelled very far. In this context Indian lexicography has a very distinguished pedigree. Even before the advent of writing, Sanskrit’s lexicographical tradition of Nighantus[4] in 3000 BC comprised thematically arranged synonyms incorporating mnemonic devices such as rhythm, rhyme and perhaps music and passed from one generation to another in oral mode (Hartmann and James 2001). (This Sanskrit lexicographical tradition was later followed for another classical language of India, Tamil, in the medieval period culminating in Akarati Nikhandu.) Some of the Sanskrit lexical worth mentiong here are: lDhanwantarinighantu, aryayratnamala, Shabdacandrika, Shabdakalpadrum, Amar Kosh, Medinikosh followed this illustrious tradition of Indian lexicography. (Most of the old Sanskrit lexcial works are word lists or thesauruses, as they are compiled subject or theme wise. Some of them have been compiled in the rhyming order. The latter method is understandable since in those days the popular format of writing was poetry, and the authors were always in search of rhymes. So much so that the tradition continued up to the nineteenth century.

Here a mention of Amar Kosh in some detail will not be out of place. Its author Amar Singh gave his celebrated work the title of Namalinganushashan, i.e., the Discipline of Names and Genders. It was also called Trikand–after its three cantos (namely 1. Heaven, 2. Earth and 3 General Words). However, popularly it is known only as Amar Kosh, to commemorate the great achievement of its author, just as the English thesaurus is better known as Roget”s Thesaurus, in all its editions and variations. The exact time of the appearance of Amar Kosh is not known. It may have been written anytime between the sixth and the tenth century ad. It has been the subject of many treatises. Its Hindi commentator Pandit Haragovida Sastri lists 41 of them. One Pandit Gunaraj is said to have translated it into the Chinese language sometime in the 6th century. Later Amir Khusro”s bilingual Khalikbari was directly inspired by it.

Hindi lexicography picked its pace in the years followed by British occupation of India and later independence in 1947. Beginning with J. Ferguson’s English-Hindi and Hindi-English dictionaries published in the year 1773 to Arvind Kumar and Kusum Kumar’s Penguin English-Hindi/Hindi-English Dictionary and Thesaurus (2007), dictionaries in standard Hindi have come a long way. Some worth mentioning are pre-independence dictionaries such as A Dictionary of Urdu, Classical Hindi and English by John L. Platts (1884), A New Hindustani-English Dictionary by SW Fallon (1879), Shridhar Kosh by Shridhar Tripathi (1894), Hindi Shabda Sagar by Shyam Sundar Das and others (1912-1928), and Hindi Shabdarth Parijat by Dwarika Prasad Chaturvedi (1914), and post-independence dictionaries such as Pramanik Hindi Kosh by Ramchandra Verma (1949), Nalanda Vishal Shabda Sagar by Naval (1950), Brihat Hindi Kosh by Kalika Prasad and others (1952), Brihat Angreji-Hindi Kosh by Hardev Bahri (1960), Hindi-English Kosh(?) (I think it is– English-Hindi Kosh) by Fr. Camille Bulke (1968), A Practical Hindi-English Dictionary by Mahendra Chaturvedi (1970), The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary by R.S. McGregor (1993) and Samantar Kosh Hindi Thesaurus by Arvind Kumar and Kusum Kumar (1996).

Looking back at the emergence of Hindi, from the all inclusive language of 11th century writings of Gorakh Nath to later development of old Hindi, local forms of speech such as Brajbhasha, Bundeli, Awadhi, Bhojpuri, etc, were the mothers which lexically, phonetically and grammatically nourished the newborn Old Hindi which grew up to become today’s Hindi in the course of time (Rai 1984: 73-129). The same mothers of Hindi now show poor state of decay and endangerment with each passing day. Hindi dictionaries have always been incorporating lexical entries from these varieties as lexical variations or otherwise but in general they have not been given due independent attention by Hindi lexicographers except for some of the big ones like Brajbhasha, Rajasthani and Bhojpuri. It is not to deny that over the years many language enthusiasts and scholars have come up with commendable dictionaries of these varieties, but in absence of any organized institutional support, technical expertise and funds, most of these dictionaries appear to be lousy jobs. Table 2[5] presents the status of the 49 varieties as discussed in Census 2001 with respect to availability of dictionaries.

Table 2: Dictionary making in varieties of Hindi

|

Name of the variety |

Available/Published Dictionaries |

|

1. Awadhi |

Awadhi Kosh by Ramajna Dvivedi (1955) |

|

2. Bagheli/Baghel Khandi |

None |

|

3. Bagri Rajasthani |

Hindi-Bagri-Hindi Kosh, CIIL Mysore (year of Publication Unknown) |

|

4. Banjari |

None |

|

5. Bhadrawahi |

None |

|

6. Bharmauri/ Gaddi |

None |

|

7. Bhojpuri |

1. Bhojpuri-Hindi Shabdakosh by Ganesh Choubey and others (year of publication unknown) 2. Bhojpuri Shabda Sampada by Hardev Bahari (1981) 3. Bhojpuri-Hindi Shabdakosh by Braj Bihari Kumar (1978) |

|

8. Brajbhasha |

1. Braj Sur Kosh in 4 vols. (based on Poet Surdas’ work) by Prem Narayan Tandon (1949) 2. Krishak Jivan Sambandhi Brajbhasha Shabdavali by Amba Prasad Suman (1960) 3. Sur Shabda Sagar by Hardev Bahari (1981) 4. Sahityik Brajbhasha Kosh by Vidya Niwas Mishra and others (1985) 5. Brajbhasha Shabdakosh by Sudhindra Kumar and Ramsharan Gaud (2000) 6. Abhinav Brajbhasha Shabdakosh by Rakshapal Singh (2006) |

|

9. Bundeli/ Bundelkhandi |

1. Bundeli-Hindi Shabdakosh by Language Directorate, Government of Madhya Pradesh (1990) 2. Bundeli Shabdakosh by Kailash Bihari Dvivedi (2002) |

|

10. Chambeali |

None |

|

11. Chhattisgarhi |

Chhattisgarhi Shabdakosh by Ramesh Chandra Mehrortra (1982) |

|

12. Churahi |

None |

|

13. Dhundhari |

None |

|

14. Garhwali |

1. Garhwal Bhasha Ka Shabdakosh by Jailal Verma and Kunwar Singh Negi (1982) 2. Garhwali-Hindi Shabdakosh by Arvind Rajpurohit and Bina Benjawal (2007) |

|

15. Gojri |

None |

|

16. Harauti |

None |

|

17. Haryanvi |

Haryanvi-Hindi Kosh by Jai Narayan Kaushik (1985) |

|

18. Hindi |

Discussed in the same section |

|

19. Jaunsari |

None |

|

20. Kangri |

None |

|

21. Khairari |

None |

|

22. Khari Boli |

None |

|

23. Khortha/ Khotta |

None |

|

24. Kulvi |

None |

|

25. Kumauni |

1. Kumauni-Hindi Shabdakosh by Narayandutt Paliwal (1985) 2. Hindi-Kumauni-English Dictionary by Sher Singh Bisht (1994) 3. Sanskrit-Kumauni-Hindi Kosh by Jaidutt Upreti (2008) |

|

26. Kurmali Thar |

None |

|

27. Labani |

None |

|

28. Lamani/ Lambadi |

None |

|

29. Laria |

None |

|

30. Lodhi |

None |

|

31. Magadhi/ Magahi |

Magahi-Hindi Shabdakosh by Bhuvaneshwar Prasad Sinha (2001) |

|

32. Malvi |

None |

|

33. Mandeali |

None |

|

34. Marwari |

None as an independent dictionary but included in Rajasthani Dictionaries |

|

35. Mewari |

None |

|

36. Mewati |

None |

|

37. Nagpuria |

None |

|

38. Nimadi |

None |

|

39. PahaRi |

None |

|

40. Panch Pargania |

None |

|

41. Pangwali |

None |

|

42. Pawari/ Powari |

None |

|

43. Rajasthani |

1. Rajasthani Shabad Kosh by Sitaram Lalas (1958-1978) 2. Rajasthani-Hindi Shabdakosh by Badri Prasad Sakariya (1982) 3. Rajasthani Lok Jivan Shabdavali (Based on Mewari) by Brajmohan Javalia (2001) 4. Rajasthani-Hindi Arthik Evam Vyaparik Shabdakosh by Sadik Mohammad (2003) 5. Rajasthani-Hindi-English Dictionary by Bhanvarlal Suthar and Sukhveer Singh Gahlot (2008) |

|

44. Sadan/ Sadri |

None |

|

45. Sirmauri |

None |

|

46. Sondwari |

None |

|

47. Sugali |

None |

|

48. Surgujia |

None |

|

49. Surjapuri |

None |

As we can infer from Table 2, most of these varieties lack any modern lexical resources. Owing to growing pressure of dominant languages in most of the social spheres of language use (even in households), rising homogenization of languages, proliferation of media in dominant languages and spread of education in dominant languages, it appears that not in too distant future nothing much will be left of their precious lexical heritage. This situation does not seem to be very different to what Skutnaab-Kangas (2000) calls ‘Linguistic Genocide’. This lexical heritage comprising of bio-cultural knowledge accumulated over millions of years which has been the core of people traditional and sustainable way of living with nature since times immemorial will be lost forever when the younger generation ceases to speak these varieties. Even those varieties, for which considerable number of dictionaries has been compiled, do not have any modern, authentic and user friendly lexical resource which can be used and accessed by general public easily and without browsing through the dusty shelves of libraries. There is no denying that the dictionaries compiled so far for these varieties, are valuable repertoire of invaluable cultural and local knowledge but unfortunately most of them are of out circulation and difficult to procure. The need of the hour is to preserve this precious lexical heritage resulting in revitalization of these varieties as well as enrichment of Hindi lexicon (as they have always done). In light of contemporary situations, it becomes imperative to document and create modern lexical resources of these languages with the aim to conserve and sustain the linguistic heritages of these varieties.

The Project

With the aim to conserve the linguistic heritage of the various varieties of Hindi, Central Institute of Hindi, Agra started the mega-project ‘Hindi Lok Shabdakosh Pariyojana’ in the year 2007. Apart from some individual efforts in the last century, so far this project has been the only institutional effort aiming to document and prepare lexical resources of all varieties of Hindi (based on the report ‘Language: India and States’, 1997, Census of India, 1991) using state of art lexicographical tools and methodologies. In order to reach wider readership and usage, the project envisages to build trilingual dictionaries (Variety-Hindi-English) in both print as well as web mounted digital formats. In the first phase of the project, 7 languages are chosen for lexical documentation viz. Brajbhasha, Bhojpuri, Rajasthani (Marwari), Bundeli, Chhattisgarhi, Awadhi and Malvi out of which work on Brajbhasha, Bhojpuri and Rajasthani (Marwari) are underway. The project is headed by Mr. Arvind Kumar as its editor in chief. The project aims to bring out these 3 dictionaries [i.e. of Brajbhasha, Bhojpuri and Rajasthani (Marwari)] by the first quarter of the year 2009.

The Methodology

HLSP employs a unique methodology and state of the art techniques for the making of these trilingual dictionaries. Each dictionary is compiled in four stages, namely:

1. Collection of lexicon in pre-formatted entry forms from the fields and published materials using thematically arranged and semantic domain oriented questionnaire developed by the project. Questionnaire based on SIL Dictionary Development Process (DDP) version 4.2 is also used at this stage.

2. Digitization of the collected data using FieldWorks Language Explorer 2.0 and Lexique Pro 2.8.6 on ultra modern computers running Windows Vista.

3. Language editing and vocabulary addition by a language expert.

4. Final editing, proof-reading and publication.

Since the focus of the project is on lexicon in endangerment, most of the data for the dictionaries is collected from linguistic field work at designated places in the language area by the members of the project. HLSP follows a line of approach that only that vocabulary will be included in the dictionaries which do not have one to one correspondence (phonetic as well as semantic) in standard Hindi. The field workers have also been encouraged to record the elicitation interview using audio recorders. The data thus collected is then processed for spelling errors, grammatical judgements, Roman transliteration and other corrections before digitization on computers. After digitization the rough draft of the dictionary is edited by the language expert. The language-edited dictionary after going through the process of subediting and final editing is sent for publication in both digital as well as print formats.

The Dictionary Format

As stated earlier HLSP plans to compile trilingual dictionaries of these varieties. A typical entry block in the dictionaries will look like this:

<Head Word in Variety and in Devnagari> <Roman Transliteration> <Grammatical Info>< Meaning /definition in Hindi> <Meaning/Definition in English>< Usage example in variety>

Every head word for each dictionary entry is supplemented with Roman transliteration following Harvard-Kyoto convention of Devnagari transliteration.

The Tools

With the advent of information technology in late 20th century, lexicography has seen a dramatic shift. Today most of the modern dictionaries are compiled using computer aided tools and technologies. This has not only made the work of a lexicographer easier but also almost devoid of errors. Keeping with the state of the art in lexicography HLSP has been using Summer Institute of Linguistics’ FieldWorks Language Explorer 2.0 (in short Flex) and Lexique Pro 2.8.6 applications for making the dictionaries. Both these applications are open source application freely available for download and use from Summer Institute of Linguistics” website[6].

FieldWorks Language Explorer 2.0

This application popularly known as Flex is a lexical and texts tools component of SIL Fieldworks 5.0 designed for organizing and studying words and texts in a language. It can be used to perform following functions on windows PC:

- Creating a lexicon of words in the language (including multilingual support such as for definitions, and multiple vernacular orthographies.) which can be configured into dictionaries.

- Creating interlinear texts in which words can be annotated as a whole as well as broken into morphemes which are further analyzed.

- Explicit links from interlinear texts to the lexicon.

- Creating a morphological grammar describing how words are broken into morphemes, and testing this by parsing words in texts and word lists. (An HTML document describing the morphology can be generated automatically from this information.)

- Building concordances of occurrences of word-forms (and eventually morphemes) in texts.

6. Elicitation of words and bulk editing of data (as described in the Dictionary Development Process).

7. Networking capability (multiple collaborators can work simultaneously).

8. Flex supports Unicode, Windows Uniscribe rendering, Graphite rendering of complex scripts, Right-to-left scripts (with some limitations that are being reduced over time).

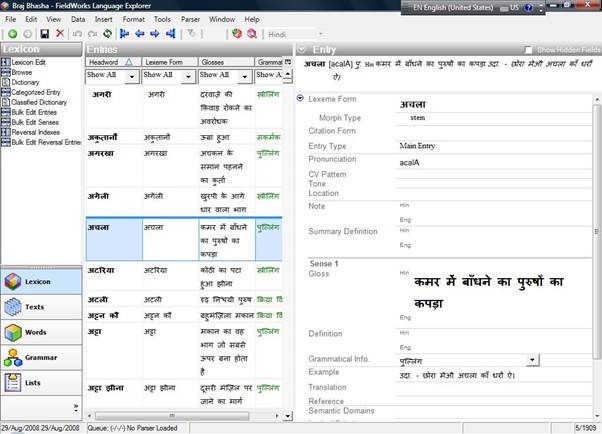

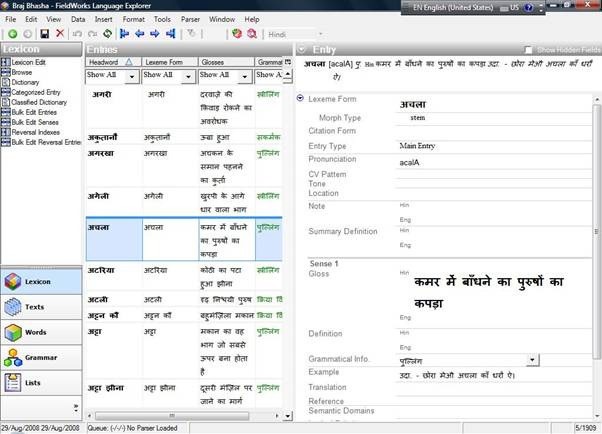

Flex comes supported with SIL DDP (Dictionary Development Process) designed to facilitate the development of dictionaries for minority languages. At the heart of the process is a list of semantic domains that can be used to collect words, classify a dictionary, and facilitate semantic research. Figure 1 shows the lexicon edit view of Flex Brajbhasha project

Figure 1 Screenshot of Brajbhasha Lexicon

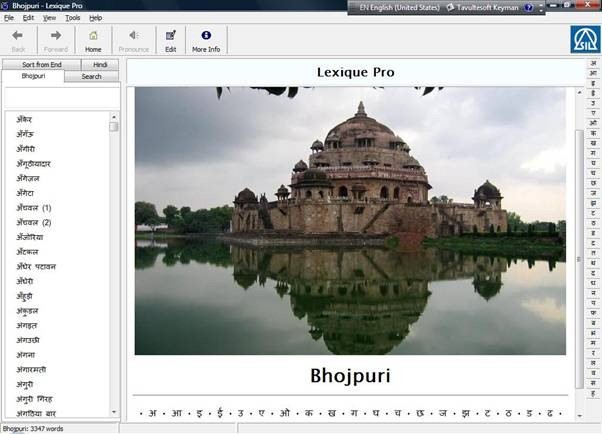

Lexique Pro 2.8.6

Lexique Pro is an interactive lexicon viewer, with hyperlinks between entries, category views, dictionary reversal, search, and export tools. It can be configured to display Flex database in a user-friendly format so that you can distribute it to others. It also allows export of the configured dictionary to office applications such as Microsoft Office 2007. It can be used to play hyperlinked audio files. Figure 2 shows the interactive view of Bhojpuri Lexicon.

Figure 2 Screenshot of Bhojpuri Lexicon in Lexique Pro

Conclusion:

In this age of globalization and increasingly disappearing global diversity in all the spheres of human society, language endangerment can result not only in the vanishing of voices but also of the vast bio-cultural knowledge and linguistic heritage. Hindi being the fastest growing lingua-franca of the nation (officially as well as unofficially), it becomes imperative that it looks back in its backyard where it grew up over the years. The development of lexical resources for varieties of Hindi will be a grand tribute to the people who gave their ‘voices’ to make Hindi stand up and run. HLSP project of Central Institute of Hindi, Agra by compiling modern trilingual dictionaries of these varieties will fill a much aggrieved gap which has left these varieties to almost abandonment and ignorance. There is no doubt that this resource development will be a win-win situation not only for Hindi but also for all the lesser known varieties of Hindi in the long run.

Acknowledgements

We would sincerely like to thank Prof Shambhunath, Director, Central Institute of Hindi, Agra for actively and vociferously supporting the cause of the project. We would also like to offer our gratitude to various language scholars who participated in our dictionary workshops, Mark and Ron from SIL international for all technical help for Flex and Lexique Pro and SIL International for encouraging the language diversity by providing open source and superb software tools. We are grateful to Prof Mira Sarin (Head of the Department), project and administrative staff at CIH, Agra for supporting it whole heartedly. Last but not the least we are grateful to Language Division, Ministry of Human Resource Development, GOI, for providing us the necessary funding for running the project.

References:

Census of India, (2001), http://www.censusindia.net/

Ethnologue (2008), http://www.ethnologue.com/

Grierson, George A. (1906), Linguistic Survey of India, http://www.joao-roiz.jp/LSI/

Hartmann, Reinhard R.K. and James, Gregory comps. (2001) Dictionary of Lexicography, Routledge/Taylor and Francis, New York

Hartmann, Reinhard R.K. ed. (1983) Lexicography: Principles and Practice (Applied Language Studies Series), Academic Press, London

McGregor, R.S. (1972), Outline of Hindi Grammar, Oxford University Press, New Delhi

Rai, Amrit (1984), A House Divided: the Origin and development of Hindi/Hindavi, Oxford University Press, New Delhi

Shapiro, Michael C. (2003), Hindi, in Cardona, George & Dhanesh Jain, The Indo -Aryan Languages, Routledge

SIL International (2007), FieldWorks Language Explorer Student Manual, SIL, Texas

SIL International (2008), Lexique Pro Guide, SIL IVB, Mali

Skutnaab-Kangas (2000), Linguistic Genocide in Education- or Worldwide Diversity and Human Rights, Mahwah, London, LE Associates

[1] In linguistic literature the term dialect is falling out of favor because of the negative connotations associated with it in colonial contexts

[2] Recognized as an independent scheduled language in 2001 Census

[3] Ancient Egyptian stone bearing inscriptions in several languages and scripts discovered by soldiers of Napoleon’s Army in 1799

[4] Nighantu is term for a traditional collection of words, grouped into thematic categories, often with brief annotations

[5] Only major dictionaries of a particular language are included here. Lexicographical works of other kind such encyclopedias, Idiom dictionaries etc are not considered.

[6] http://www.sil.org/

Comments